Diocese Plans to Close Historic Riverside Catholic School

Parents mobilize to save 107-year-old St. Francis de Sales amid financial challenges, declining enrollment.

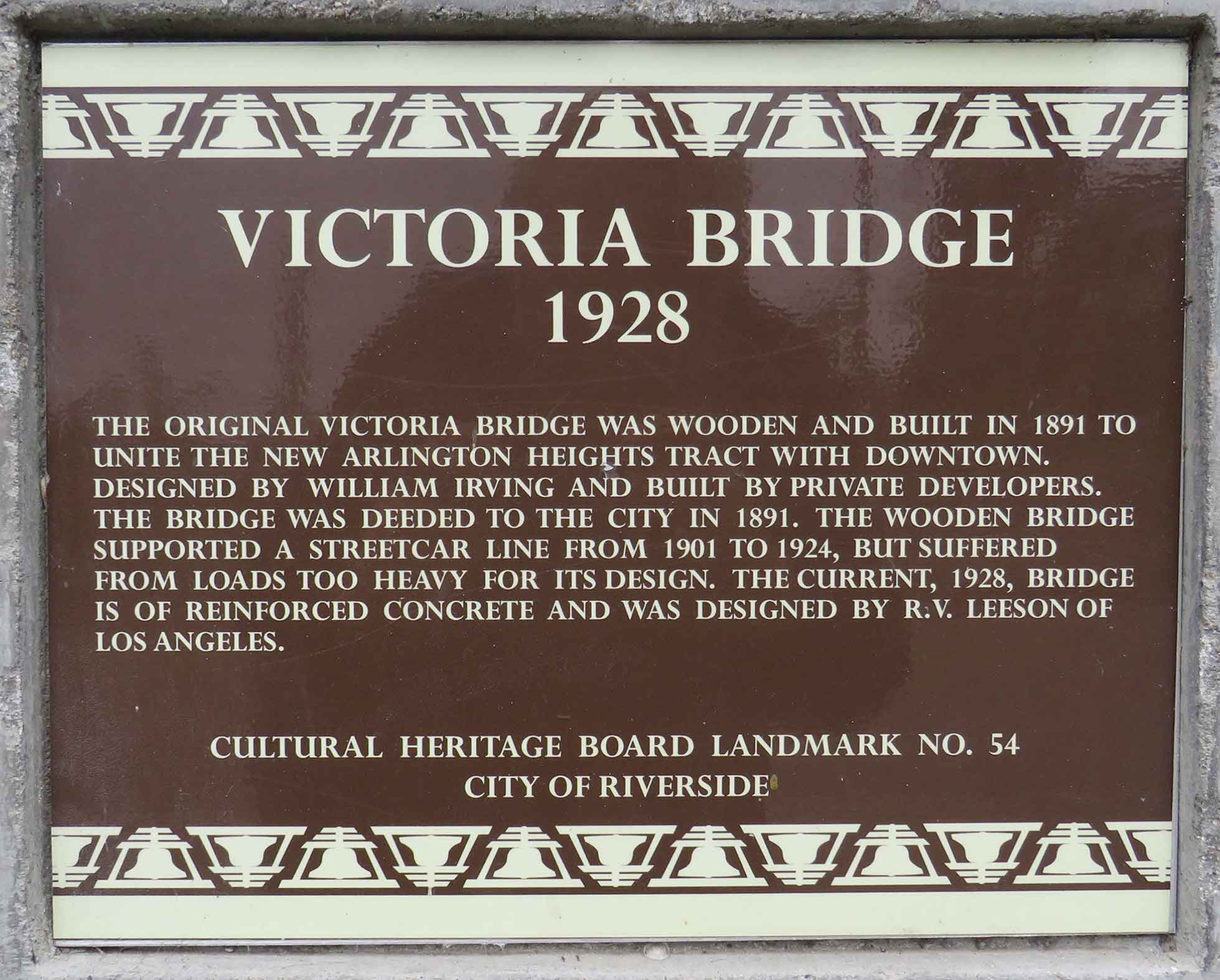

Celebrated as a feat of engineering and a symbol of community effort, Victoria Bridge has traversed the challenges of time to serve Riverside's evolving transportation needs.

The old Victoria Bridge, built in 1891, closed on February 28, 1927. The Riverside City Council took this action as the bridge was deemed unsafe. Long detours around the closed structure made area residents unhappy and vocal. Yet the city did not have the funds to properly repair it nor to erect a new bridge.

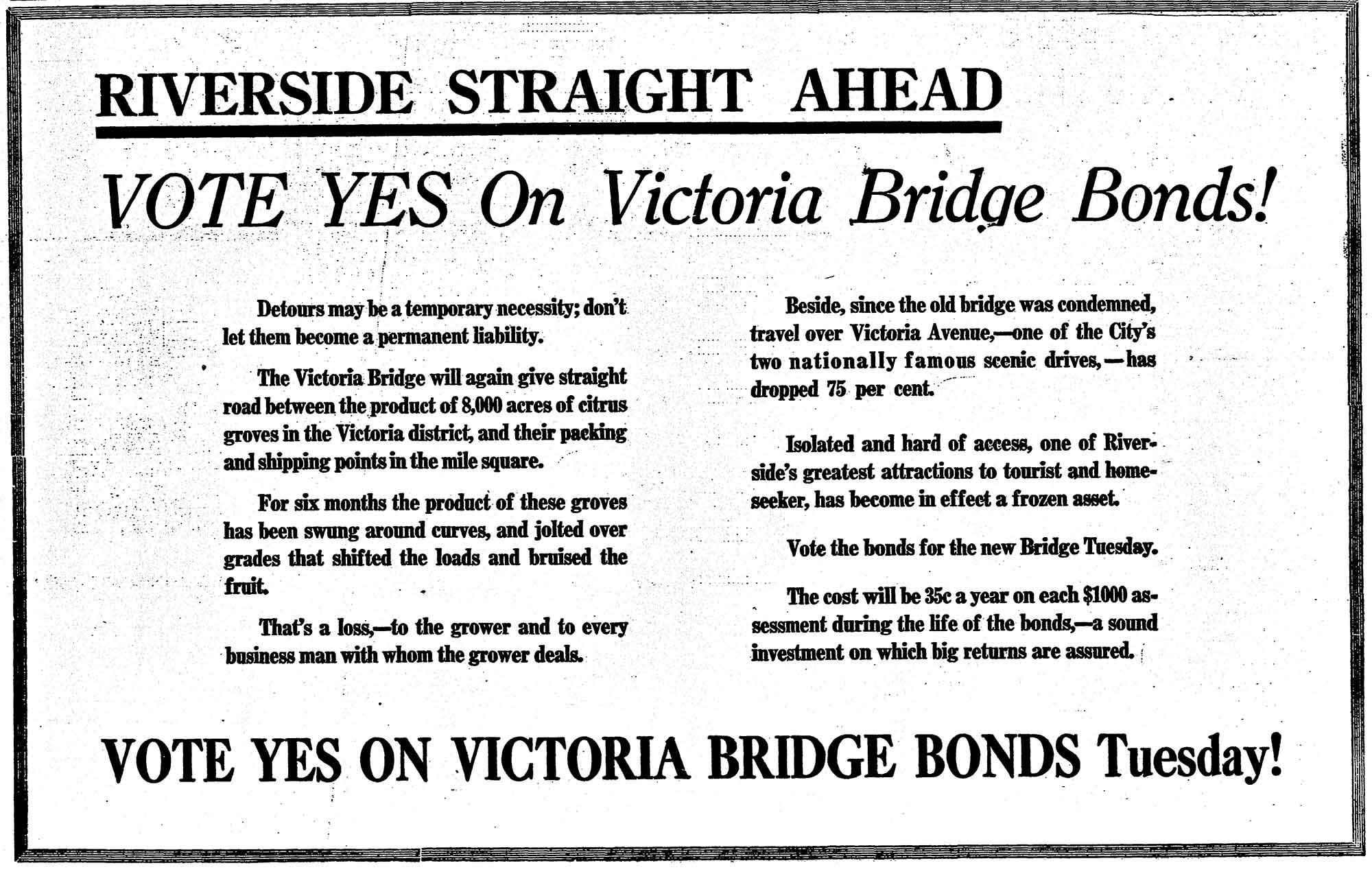

A special election on June 21, 1927, considered four bond issues for civic improvements, one being funds for a new Victoria Bridge. Letters to the editor and ads strongly supported the bond measure and urged the citizens to show their loyalty to Riverside by voting “Yes” on all the issues. Advocates pointed out that the bridge was important for hauling the oranges from the groves to the packing houses as part of the $10,000,000 Riverside citrus industry. They pointed out that the bridge was a necessary outlet for traffic and transportation important to the entire city.

The citizens of Riverside did not agree, and all four bonds were defeated. The bridge bond received a simple majority approval but failed by almost 600 votes for the needed two-thirds majority. The backers of a new bridge soon went back to work. On July 6, a committee brought a resolution before the City Council asking for the bridge to be constructed under a district assessment plan comprising all territory in the city that benefited from the bridge. They pleaded that one of the largest and most important parts of the city was marooned and isolated since the old wooden bridge had been closed. Everyone attending the council meeting signed the petition, and the council approved the plan. Now, the task was to decide on what areas of the city benefited from the Victoria Bridge.

Robert V. Leeson, the consulting engineer from Los Angeles, had already worked up construction plans and estimates, and on July 12, the council authorized work to commence as soon as possible. Details on the assessment districts needed to be finalized. Some areas took a very parochial viewpoint that the bridge did not directly benefit them, so they should not be included – a type of "not in my neighborhood" perspective.

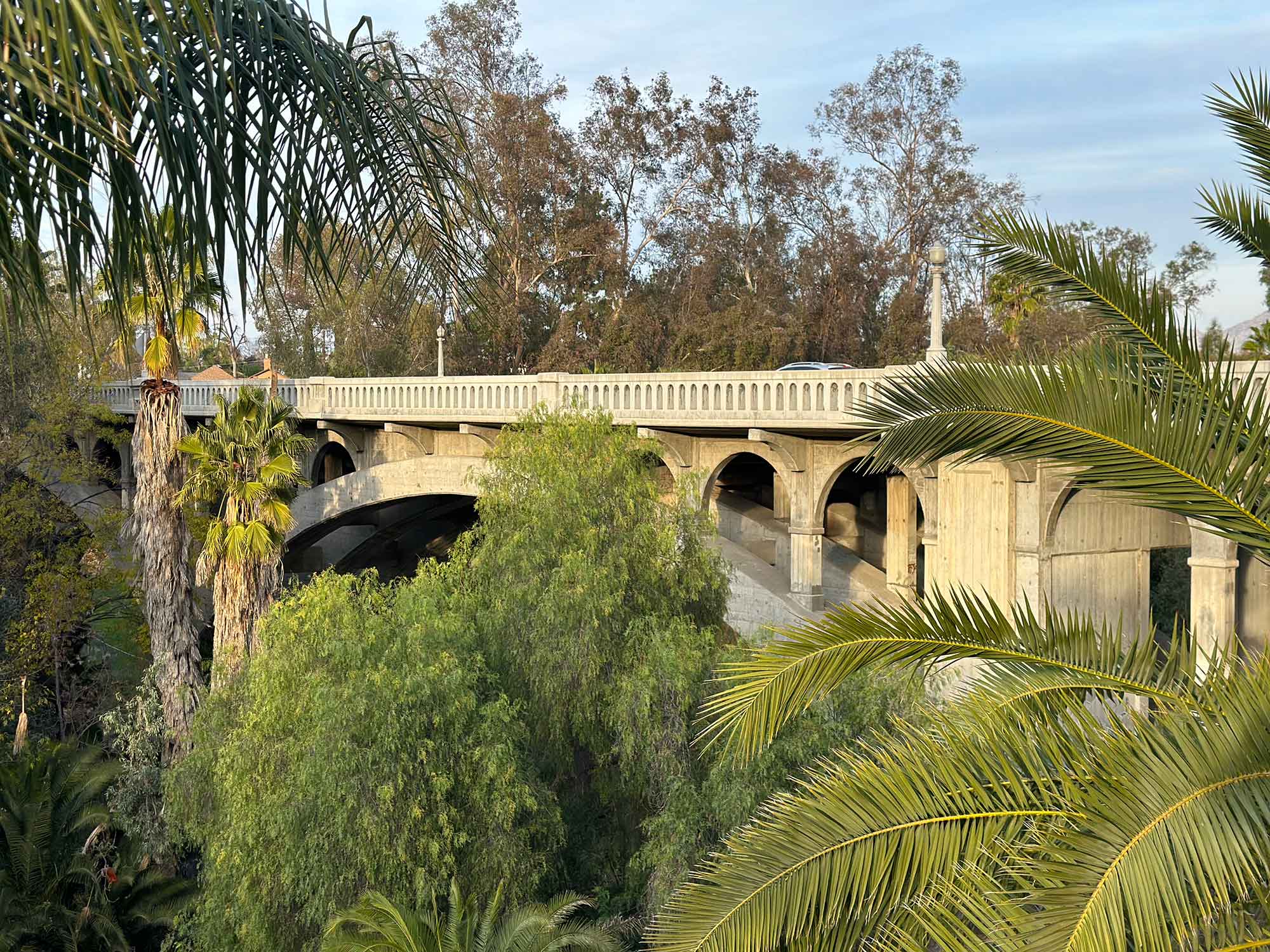

By the end of 1927, the council was ready to proceed and set January 17 for bids to be opened and approval given. On that morning, DeWaard & Son, a Los Angeles contracting firm, won with a low bid of $74,307.10. The construction specifications called for a reinforced concrete bridge of three spans, each span measuring 120 feet. The roadway would be 30 feet with two five-foot sidewalks. Ornamental railings and lighting stands would decorate the bridge. Leeson estimated that 20,000 sacks of cement would be required, 235,000 pounds of steel, 2200 tons of sand, and 5000 tons of rock. The bridge extended 522 feet from end to end over the arroyo. The roadway would be strong enough to support a 20-ton truck. From the bottom of the piers to the floor of the bridge, the highest point was 78 feet above the ground.

Contractor DeWaard & Son pushed ahead, hiring local firms Hayward Lumber for the lumber and Riverside Cement for the cement. Work began in the middle of February. As work progressed, the old timbers and planks were removed, and new forms were built for the reinforced concrete.

The last remaining gap of roadway was poured on August 1, with only some of the sidewalk and ornamental railings left to finish. All electric and telephone cables were installed and concealed in the ornamental guard rails. By the middle of August, a mere five months after work had begun, the bridge was temporarily opened to traffic with the understanding it would be closed for the formal opening sometime in September.

Two bronze tablets were prepared to be placed on each end of the bridge. The one on the north end related the history of the earlier bridge and the memories of William Irving and Matthew Gage, who were responsible for the first span. The tablet on the south end contained information on the new bridge.

September 18, 1928, was an exciting day in Riverside as city officials and citizens gathered for the dedication of the new Victoria Bridge. John Raymond Gabbert, editor of the Riverside Enterprise, acted as Master of Ceremonies. DeWitt Hutchings, Frank Miller's son-in-law, opened the festivities by reading the poem “The Bridge Builder.” Mayor E. M. Dighton formally accepted the bridge for the city of Riverside. The mayor declared, “The new bridge is splendid. Its design well fits into the rugged grandeur of its locale, and its arches from a distance outline vista of outdoor beauty.” At the end of the ceremony, J. Norman Irving unveiled a bronze tablet honoring his father, William Irving, the designer of the first bridge, and in honor of his uncle, Matthew Gage, who was responsible for the building of the first bridge.

In praising the new bridge, the Riverside Daily Press declared, “Officials and Citizens Assemble to Commemorate Completion of Notable Improvement, Designed to Last for All Time.” That statement proved not to be true. By 1980, Caltrans warned that heavy traffic weighing more than the 20 tons the bridge was built to handle was weakening the structure. Weight limits were posted for traffic over the bridge. By 2005, the bridge needed to be reinforced for traffic and for earthquake safety. On June 27, the bridge was closed, and traffic detoured for about half a year as the bridge was reinforced and strengthened.

Today, Victoria Bridge still stands and carries traffic linking areas of the city separated by the Tequesquite Arroyo. The Cultural Heritage Board declared the bridge as Riverside City Landmark #54. If you have not driven over this Riverside City Landmark, take a ride someday soon along Victoria Avenue and over this splendid bridge.

Let us email you Riverside's news and events every Sunday, Monday, Wednesday, and Friday morning. For free