🗞️ Riverside News- January 8, 2026

Ward event policy change, Fairmount armory brewery approved, convention center EIR certification upheld...

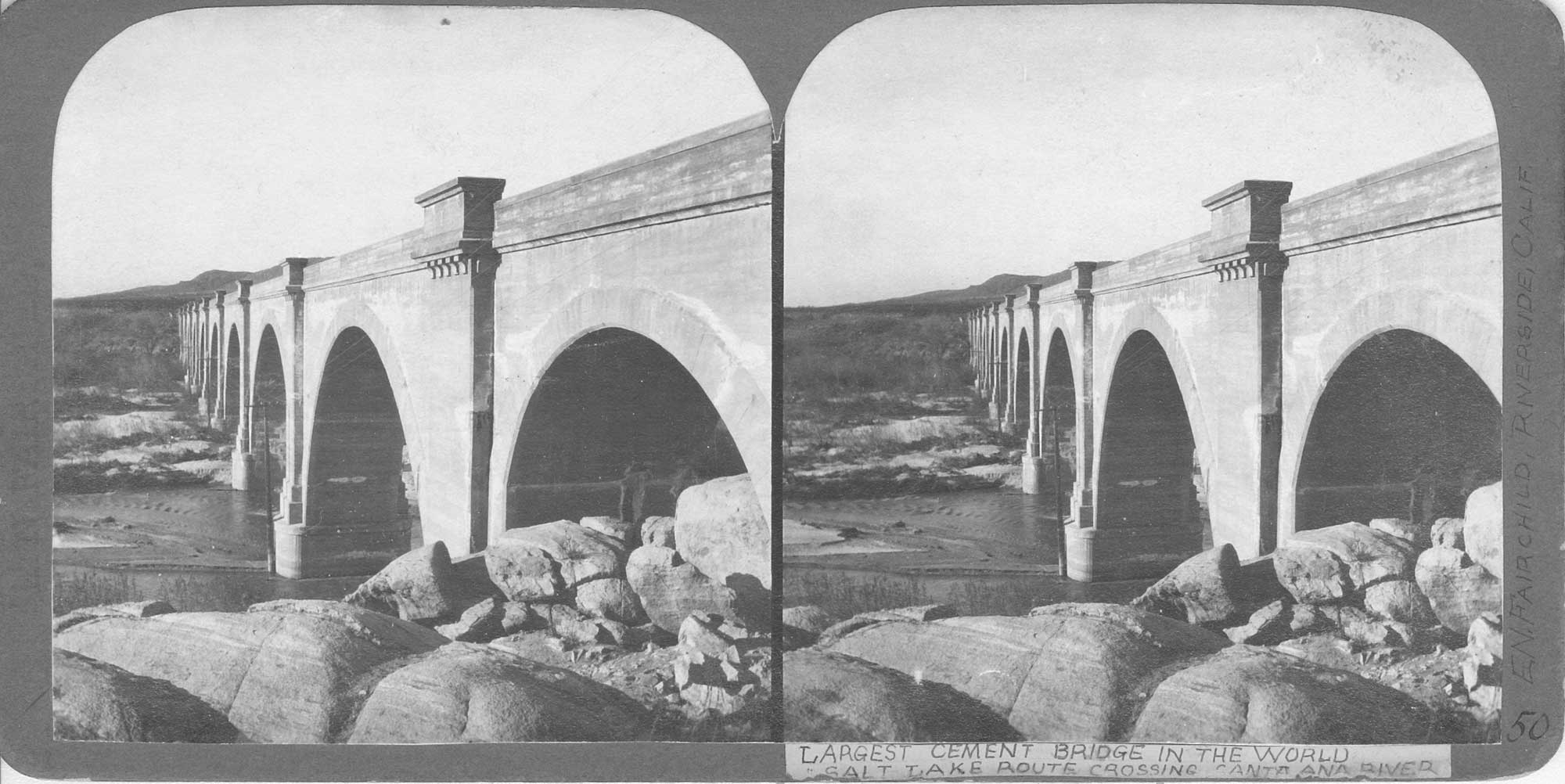

Constructed as the longest concrete bridge in the world in 1904, Riverside’s Railroad Bridge not only transformed local transportation but also became a landmark of architectural beauty.

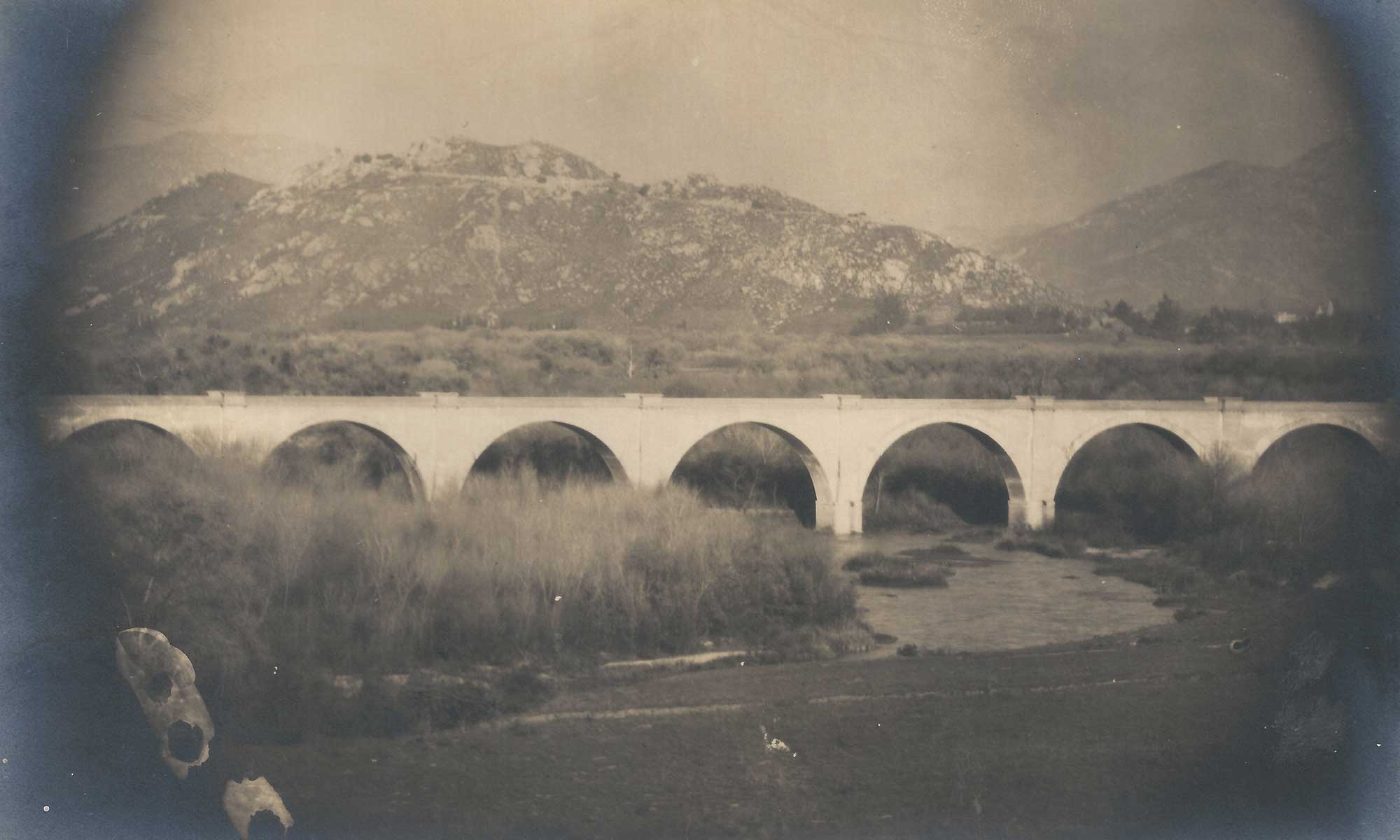

Looking southwest from the heights of Mount Rubidoux, a bridge of remarkable beauty and engineering stretches across the Santa Ana River. Located at the Narrows, the site at which, in both 1774 and 1776, Juan Bautista de Anza crossed the river on his overland journey from Tubac, Mexico, to the San Francisco Bay area, this bridge was built by the San Pedro, Los Angeles, and Salt Lake Railroad in the very early years of the Twentieth Century. Today, the site borders the city of Riverside’s Martha McLean - Anza Narrows Park.

Historical markers commemorating Anza’s crossings are located on both sides of the Santa Ana River. On the west side, near one of the fairways at Jurupa Hills Country Club, is California Registered Landmark No. 787 plaque dedicated in April 1964 by the Riverside Pioneer Historical Society, De Anza Caballeros, Native Daughters of the Golden West Jurupa Parlor, Native Sons of the Golden West Riverside Parlor and the Rubidoux Chapter N.S.D.A.R. Located in the Martha McLean-Anza Narrows Park on the east side of the river is a tablet marking the DE ANZA TRAIL 1774. This tablet was placed there in 1942 by the De Anza Trail Caballeros. Looking northwest from this tablet is a picturesque view of the railroad bridge.

The chosen route proceeded north from San Pedro to Los Angeles and east towards Riverside. The rails from Los Angeles passed through Whittier Junction, Clayton, Hillgrove, Rowland, Walnut, Spadra, Pomona, Sun Sweet, Ontario, Galloway, Wineville, Bly Junction, and Pedley before entering Riverside and then turning north. Some of these names are familiar, while others have been absorbed into neighboring cities. To enter Riverside, the line needed to cross the Santa Ana River. The chosen location was across the Narrows, about one and three-quarters miles below the foot of Mount Rubidoux. Early reports called for the longest concrete arch bridge in the world.

On Thursday, October 23, 1902, the Daily Press led with their story: “Greatest Bridge Ever - Salt Lake Road’s Bridge Across the Santa Ana Will Be a Great Feat of Engineering. The bridge would have a total length of 900 feet. The plans called for eight arched spans of 100 feet each and two approaches at each end of 50 feet. The bridge would rise 60 feet above the river. A contract for 12,000 barrels of cement was signed with Colton Cement Works. The work was expected to start the following Monday. The newspaper glowed with praise: “The big bridge will give Riverside some valuable advertising. All the engineering and railroad papers will contain descriptions of it, and the bridge will in all cases be associated with Riverside.” The work excavating the piers would start first. These piers would be fourteen by twenty-eight feet and be sunk down to bedrock, estimated to be ten to fourteen feet below the river bottom. The early estimate was that the work would take six to eight months before rails could be laid.

Meanwhile, work was progressing on the bridge foundations and the line to Riverside. On December 11, 1902, the newspaper stated that ties were being laid on the grades from Pomona to Riverside, and rails would follow shortly. At the Santa Ana River, the work was still confined to the foundations.

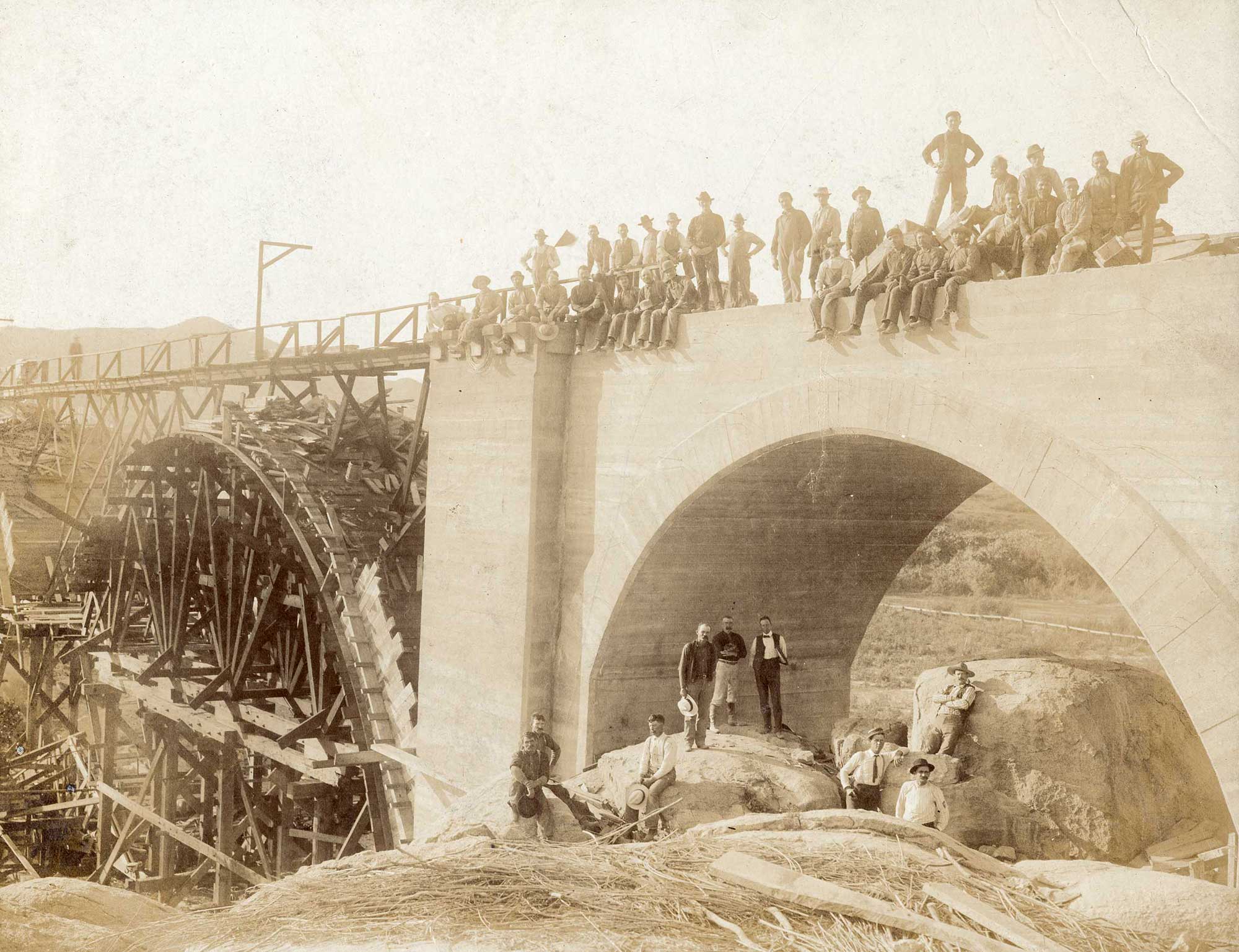

At about 9 a.m. on Tuesday, February 3, a special train left Los Angeles carrying officials, dignitaries, and friends from the Salt Lake Railroad on an excursion to the Santa Ana River bridge site. They arrived at the crossing at about 1 o’clock to thoroughly inspect the bridge's progress. Congressman M. J. Daniels, H. T. Hays, and Frank A. Miller joined in the inspection from Riverside. Another eight to ten months were needed to complete the bridge. In March, the wooden frame timbers around three of the eight arched spans were in place and ready for the concrete. At that point, a dozen steam engines and 190 men were employed at the bridge work, with more men and equipment to be added as the cement work started.

All but two of the piers were in by May, and the excavation of the last one was stated to be almost complete. Excavating the piers to reach down to the bedrock was challenging. The natural flow of the river and quicksand also provided a unique challenge.

By the middle of November, the bridge was almost complete, and it was just in time for an inspection by the Southern California Engineer and Architect Association members who were meeting in Los Angeles. As the guests of J. Ross Clark, forty-five delegates left Los Angeles at 8 o’clock on a special train taking them to Riverside. They arrived at the big concrete bridge on the Santa Ana an hour and fifteen minutes later. Soon, they climbed over the bridge, inspecting its features and enjoying the grand scenery. A reporter on the scene recounted that when they touched the bridge, they could hardly express their mingled delight and surprise.

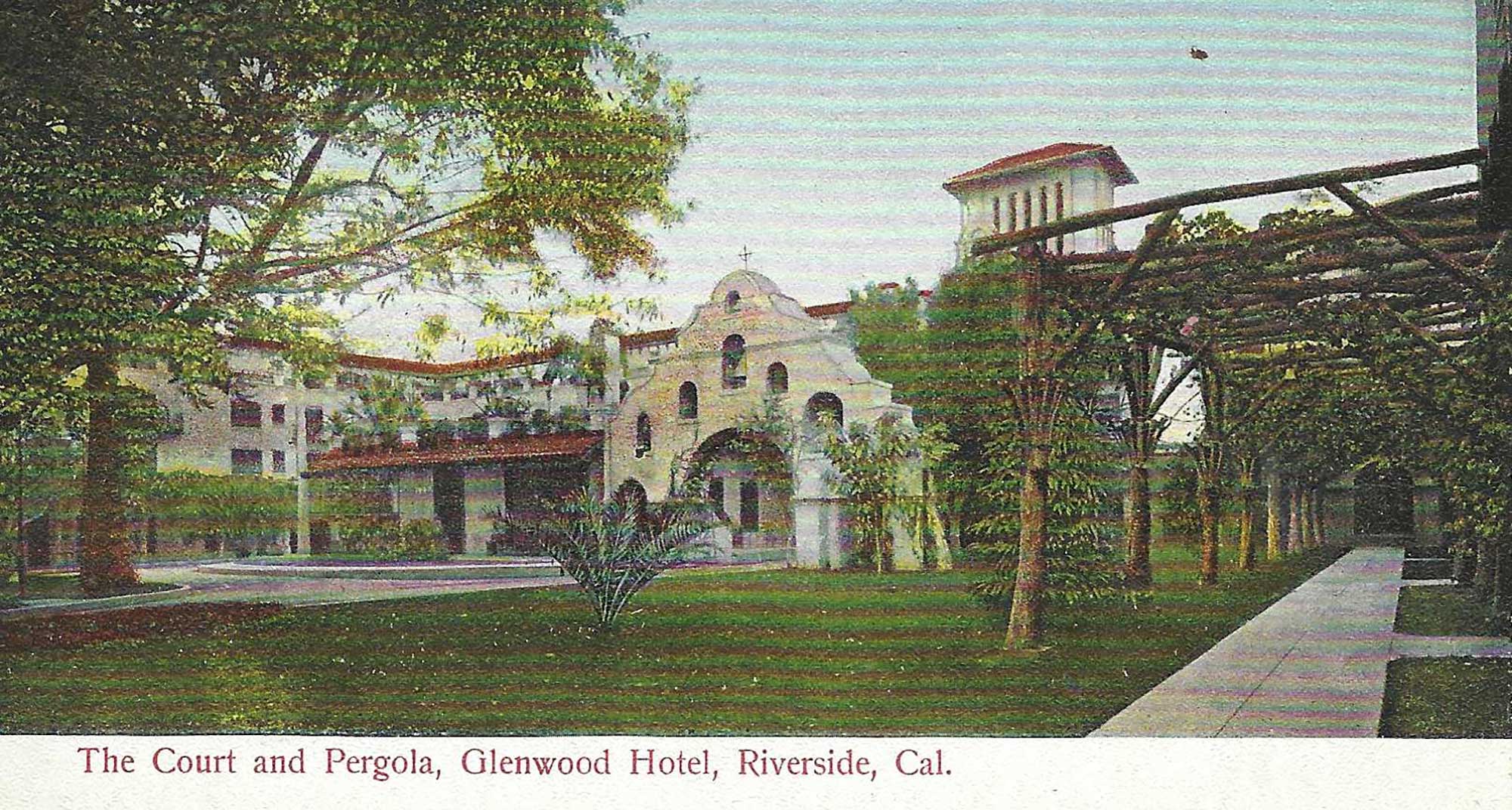

After the inspection, the guests were taken by tallyhos to the New Glenwood, where they sat down to a banquet. Following the banquet, the group was given a hotel tour before returning to the bridge and their train ride back to Los Angeles.

At last, the main work on the magnificent concrete bridge was completed. The first train was run across the bridge at 2 o’clock on Saturday, January 9, 1904. It was one of the Salt Lake Railroad construction trains that ran across on rails sustained by many ties. The final ballast of thirty inches of gravel was not yet in place.

Salt Lake Railroad officials invited guests from Los Angeles to cross the newly completed bridge to Riverside. The group left Los Angeles at 10 o’clock, ate lunch on the train, and returned by 2:30 that afternoon. Two weeks later, another special train pulled by Engine 101 made an inspection trip to the bridge. To show the excellent condition of the roadbed and track, the train made the return trip to Los Angeles, a distance of fifty-two miles, in forty-five minutes. The general manager of the Salt Lake, Ralph Wells, commented, “I guess we were going pretty fast.” The report stated, "The engineer in the cab took another hitch in his overalls, opened the throttle still wider, and how that car was whisked over the road was special.”

With the completion of the bridge, the Pachappa Hill cut, and the new depot, special ceremonies were held on Saturday, March 12, 1904, officially welcoming the Salt Lake Railroad to the city of Riverside. Mayor C. L. McFarland extended greetings from the city to the new rail line. Riverside had the longest concrete bridge in the world!

Today, the Union Pacific, having absorbed the Salt Lake Route, still operates freight trains daily over this magnificent and unique structure. The bike trail of the Santa Ana River Trail passes under the easternmost arch of the bridge. One hundred and six years after completion, this bridge still stands strong and carries tons of daily rail traffic. Those prophecies of the early engineers and builders so far have held up. Take a trip to Martha McLean - Anza Narrows Park, walk down to the bridge, and view its beauty and strength. Watch and listen as a mighty freight train passes overhead. Climb up Mount Rubidoux with a pair of binoculars and see how the bridge picturesquely stretches across the Santa Ana River. Those early photos and postcards captured a magnificent and picturesque scene that advertised both the railroad and Riverside.

Let us email you Riverside's news and events every morning. For free!